Book Reviews

Every writer reads. These are some of my brief impressions and thoughts on some of my most recent science fiction and fantasy reads. Spoilers are ahead, though I will try to keep big reveals to a minimum!

For reminder of upcoming book reviews, subscribe HERE.

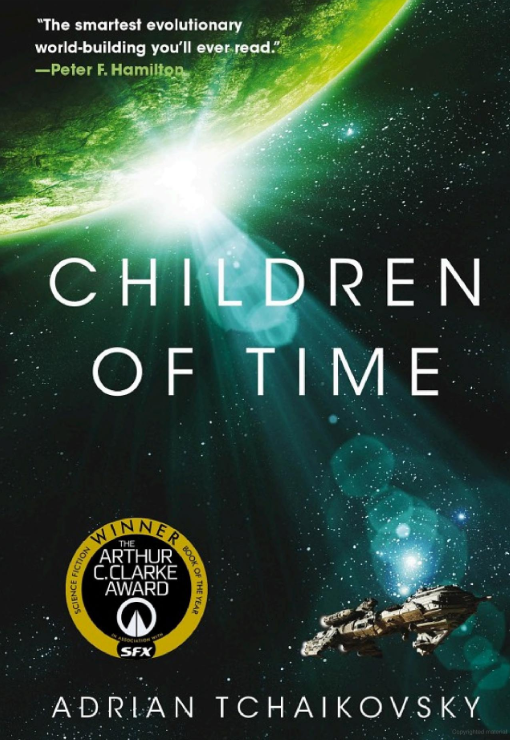

Children of Time

I am a decade late to the party, but I can’t say nothing about my most recent read, Children of Time, by Adrian Tchaikovsky. Published in 2015, read by me in 2025, the comment on the cover says it all:

The smartest evolutionary world-building you will ever read.

So much of science fiction in my reading experience takes place in the realm of physics: spaceships, laser beams, new weapons, new ways to travel the universe, teleporters, and interdimensional rifts. I love all of that, but this book delivered something I didn’t know I needed: a reminder that the biological sciences have as much to offer us in the realm of science fiction and imagination as any spaceship.

Don’t get me wrong, this book has both. There is a generational spaceship too. I won’t be giving much of anything away, as you learn this in the first few pages, but humanity has fallen. After rising to heights our current civilization can only dream about, a galaxy-spanning empire comes to a halt. It still relied on Earth, and Earth fell to warfare and the inability to see eye to eye.

The remnants of that civilization crawl their way back to space travel over thousands of years and encounter the genetic legacy of our tampering with other planets. That alone would make this book worth the read, but our author makes some decisions which are rare, outstanding, and work.

Told from two points of view, one third person limited and close, a human who wakes and sleeps through the millennia of our tale; and the other an omniscient third person point of view, rarely in use these days, it is the only reasonable way into the head of a sentient race of spiders. Because that is what Portia and her kind are. Uplifted and modified by us, we watch their history and learn about them and their stark, radical differences from us through their development, with the inevitable question of what happens when these two species meet?

This book took evolutionary biology and the technological evolution of a completely different species places I couldn’t have imagined. It threaded the needle of just enough information about both stories to keep me hooked, wanting to know more about the final destiny of the human race while I was reading about them, but still missing Portia and her eight-legged friends. Then, while reading about Portia’s people, it kept me wondering how their evolution would go, and oddly rooting for them in the inevitable confrontation with our species. (I’ll tell you for free that it doesn’t go down the way you think, and the ending is a brave, fascinating conclusion.)

There are other books, on order and on the way to read, but even if you don’t finish the series, this book was truly worthy of its Hugo Award.

5/5

Empire of The Vampire

by Jay Kristoff

I have been sitting on some book reviews for the last couple of months that I want to start putting out into the world. My luck has turned, and after a successful completion rate of maybe 20% in the previous dozen travesties that were bound between covers, (I’m new to DNFs) I have hit a smooth road of truly outstanding books with 100 % completion.

Out the gate today, I am going to recommend with a solid 4.8/5.0, about as much fun as I’ve had reading a book in a long time that wasn’t a reread, Empire of the Vampire, by Jay Kristoff. I have seen reviews that damn this book (pun intended), and if I stood it side by side with Tolkien or Rothfuss, I would have to judge it differently. Not worse, just differently. Empire of the Vampire is pure fun.

It is well written, but it is not aiming to be high literature. It shouldn’t be compared to those pieces. It served to remind me reading is supposed to be fun.

Basics: the world is our world, more or less. The exact place is not “France,” but it’s French. The exact time is not pre-medieval, but it has 1200s trappings. It isn’t a Christian world, but well... yes, it is, with a few new overlays. It is familiar in a way that I took as wonderful shorthand for understanding something different with the scent of the accustomed.

In this not-France, not-1200, not-Judeo-Christian world, there are vampires. More or less as we understand them. Super-fast, super-strong, telepathy and such, but broken down into different families of powers, almost in a way that my brain was able to see video game classes overlaid on them. The good guys are like Blade, or the Marvel universe; day-walking half-breeds who need an elixir to not eat us and turn evil.

Daysdeath happens. For some unexplained (and better for not being explained) reason, the sun is blocked and vampires lose their greatest weakness and start to take over the world. The problem becomes all the undead they created along the way. They lose control over them, and now... their food source (us) is in danger.

Basic out of the way, the main cast consists of some expected fare: knights who are half-breeds, nuns and prioresses, a grail-seeking team wanting to save the world. I’d give more characters, but it’s a little spoiler to explain. We follow Gabriel de Leon, and in the first few pages, we’re given a frame story I deeply love. He is the last living vampire hunter, who won by killing the most powerful vampire lord, the Forever King—but... he is captured and telling his tale while awaiting execution. Did we all win? Did just he win? We aren’t told. (Hence you must read to find out.)

Told through flashbacks, the story is a 70/30 mix of familiar/inventive and hits all the notes of exciting fantasy, with powerful magic, swordplay, and antiheroes to boot. I have ordered book 2, preordered book 3, and must say: if you are looking for a light read, a fun read, and a thing to do this weekend, grab this one now.

Dragon Rider by Taran Matharu

Tropes Done … Pretty Well?

Have you ever read a fantasy novel where you knew, within 30–40 pages, everything that was going to happen—but you mostly didn’t mind? That was Dragon Rider by Taran Matharu for me.

I picked this one up at a used bookstore near me, drawn in by the cover art—a rarity these days, as I find modern fantasy covers tend toward the boring and unimaginative. But, of course, the book is called Dragon Rider, so... in we went.

The story follows a young male protagonist in a setting that isn’t exactly European or Tolkienesque, but still feels very familiar. While the world-building offers some new trappings, the cultural underpinnings and fantasy tropes are well-trodden ground.

The hero meets a beautiful girl (who I guessed early on would be the love interest—and possibly reject him later), encounters the dragon riders, and begins to learn just how hard it is to become one. He struggles to bond with animals—the core magic system of the book—and soon discovers that the ruler’s son and grandson are plotting his demise in order to seize power.

So far, so standard.

And I don’t mean that negatively. The prose flows smoothly, and the characters are... mostly likable. I did find it hard to connect with the main character, and something else kept nagging at me: I wasn’t entirely sure this book knew its own genre. There were moments when I wondered if it was actually meant to be young adult.

The protagonist is young, it’s a standard hero’s journey and coming-of-age arc, and the plot is very predictable—not bad, just very recognizable. The fate of the world hinges on the actions of someone under twenty. His friends are also young, and they’re learning and growing together. You know the book.

Beyond that, the magic system is fairly engaging: bonded riders link to animals (from mice to dragons), gaining strength, stamina, and even spellcasting abilities depending on the bond. While the book has hints of epic fantasy, it leans more toward political / coming-of-age.

And... it’s good?

A solid 4/5. I would recommend a buy and read, but it lacks something meatier to push it higher. I’d recommend it as a fast, easy read—with short chapters, a breezy pace, and light stakes. It’s a snack of a book: not romantasy, not heavy epic fantasy, but a traditional hero’s journey wrapped in a light political fantasy shell.

Furry Logic

Did you know that sea turtles can detect magnetic fields with such precision that they can steer themselves back to their beach of birth a decade after setting out to sea? Did you know that ants can count? Did you know that bees can eyeball an angle better than I can measure it with a protractor?

I haven’t done many book reviews of late. Book reviews, for me, are not a matter of course. I tend to do them when a book stands out. I just finished a book last night that achieved exactly that.

Furry Logic: The Physics of Animal Life by Liz Kalaugher and Matin Durrani is an absolute joy to read. They cover the merged fields of physics and biology—heat, forces, fluids, sounds, and more—with a solid eye for clarity and inspiring awe. My background as a physicist makes the science immediately understandable to me, but every chapter has a perfect preface that provides what you need to know to understand that every day we should question what it means to be “top of the food chain.”

They cover the furry friends we call pets, like cats and dogs and their moisture retention after a swim, and they delve into the sometimes mysterious world of insects and how they achieve the impossible, like an army corps of engineers every day.

Just one example illustrates the amazing content of this book: Did you know bees can detect electrical charge? Did you know plants are electrically charged to let bees know whether previous bees have landed on them, how long it will take to recharge their nectar, and whether they should move on to other flowers? Bees have senses humans do not seem to possess, creating a simple communication structure that benefits both species. Flowers get to reproduce, and bees get to eat. This blew my mind, but it was not even close to the most amazing pieces of science in this book that illustrate how complicated the structure of our world is.

Filled with examples and historical visionaries of science—some lost to the mainstream over time, but shown in their best light in this book—Furry Logic will make you wonder how many more discoveries, which we couldn’t have fathomed a few decades ago, await us in the future as specialists continue to peel back the layers of biological complexity in our world.

4.5/5.0. Grab a copy today.

Black Sun Rising, By C.S. Friedman

I recently reread this book, the first in the Coldfire series, and a long-standing favorite of mine. Now clocking in at about 35 years old, it’s always interesting to see how something ages both in reality and in our minds.

Gerald Tarrant, my favorite single “bad guy” in fantasy—or at least it seems that way to me—still shines off the page. Damien Vryce, his counterpoint in the book and the series' beacon of right, remains undefeatable in his moral stance on what is right. They are the answer to what happens when an immovable object meets an unstoppable force.

The book belongs to the science fantasy genre, something that was far less common 35 years ago, though it is its own sub-genre now. It lands firmly on the dark fantasy side of that spectrum.

The planet Erna resembles Earth at first glance but obeys starkly different laws of nature that fuel magic. Let’s just say, be careful what you believe in—or fear. There’s no substantial technology in this book beyond what you would find in the generalities of medieval times. The atmosphere is dark and brooding, and the world is broken and filled with the hopeless. While it isn't technically horror, there are moments steeped in grisly, stomach-churning ichor. The malevolent creatures of this world are closely tied to the psyche of its human inhabitants, such that fear itself will result in even more horrors.

The relationship between the two protagonists, Vryce and Tarrant, has a kind of argumentative repetition. They will debate but make little headway, as they stand on opposite sides of nearly every issue. However, the circumstances of the world make for strange bedfellows. Some people find these circular, repeated arguments boring, but for me, they keep the tension between the characters alive. They make you want to read every one of the books in the series to see if Vryce can win Tarrant over to the side of true good.

And that is the real question. More than the journey, more than the saving of a world, the question this book poses is: can someone save another man’s soul? The answer that Friedman provides is what brings me back to the series after years away. I’ve read it three times; I am sure I will read it again.

If you are looking for a book that helped launch a genre and establishes itself as more than just another grimdark, Black Sun Rising is for you.

All these years later, for me, it stays 4.8/5.0.

The Empire's Ruin (Ashes of the Unhewn Throne, Book 1)

I am a new reader of Brian Staveley’s work. I regret to admit I had not seen his previous trilogy when it hit the shelves and haven’t read it yet, though it is on my to-read list now. I can’t recall where I picked up The Empire’s Ruin, and I can’t remember when, though it was only published in 2021.

If you are someone who is tired of the same tropes of rolling hills and forests hiding the fantasy epic you are seeking, then this is a good spot to stop and have a read. The writing is evocative of place, something hard to do. Instead of forests and rolling green hills, we are given two stories running side by side: sea travel and a swamp land, designed as if the worst of Venice had sunk into a quagmire.

Dombang, the core city in which this portion of the tale takes place, is terrifying. They worship death and laud horrible ways to die. It’s a city replete with bodies floating in the canals, constant combat, little trust, and plenty of intrigue and murder. Moreover, they know for certain, as does the reader, that their gods are real and walk those swamps if you know how and where to look.

Culture follows to a fair degree from these feelings of location. What buildings are made of, how religion operates, what is important to people, and the conflicts they have stem organically from what is set up as the background. This worldbuilding is at its best, as it is in service to the story, not just for the fun of it.

The story also hinges around the core concept that has shaped empires for centuries: speed of travel. Portals and flight, now both lost to a dying empire, must be rediscovered, or the empire will die. Imagine if Rome lost her roads, or a modern empire its telecommunications.

To tell this tale, we get to follow along with several superpowered characters, but despite their powers, the risks they take feel real, and their wants and needs feel genuine.

Ashes of the Unhewn Throne was a book I needed to find, as I have been very disappointed in many science fiction and fantasy books I have picked up of late. Gwenna Sharpe, our Kettral (massive bird) flying superstar, is a perfect mix of powerful, broken, badass, and trying to rebuild herself, as every hero needs. Through her arc, he masterfully, if somewhat self-evidently, uses clear “yes, but” or “no, and” storytelling structures to heighten the tension throughout the story.

Some people say you have to have read previous books to pick up this one, and when I get to the earlier ones, that may be true, but I can confidently say it caught my attention and drew me in on its own, without needing anything more.

It was the book I needed right now. It’s the book we all deserve.

Time Enough for Love

Robert Heinlein is about the biggest name you can get in the history of science fiction. I have read, I think, all of his works at least once, but of all his pieces, for some reason, this one stands out the most. Despite the futuristic settings of his stories, Heinlein's writing often delved into timeless questions about the nature of humanity, morality, and the meaning of life.

Descriptions of technology and scientific concepts in his work grounded his speculative fiction in a sense of plausibility and realism. The impact on society from the changes made always felt real. This book is no exception. How would society treat a progenitor of more than half the human race, who is himself ancient beyond fathoming?

(Be kind; the book was written in 1973. Though his technology isn’t that bad off.)

The main character, Lazarus, named for the biblical figure of course, is a 2,000-year-old man. To grossly oversimplify the book, which is fairly long, it asks the question of what is the point of living when you are immortal, and have all the time in the universe before you? When you have done it all, seen it all, what is next? Does life derive its purpose from its finite nature? Does it derive its purpose from interpersonal interactions? From threat, and living on the edge of possible death?

You may not like the answers he gives; in fact, there are some very strange twists in this tale that don’t work for me at all, but the idea of a person who has been alive for so long is more than enough to carry it through. Lazarus, and his many descendants whom he interacts with in the book, are oddly self-similar echoes of their living ancestor. There will be a lot that offends modern readers about who he chooses to sleep with, when, and why. It will make you hate the man that science and chance selected to live forever.

But if a book is not to make you feel, what is it for? It is not the greatest book written; it is not the greatest book about an immortal, but it is a book that has stuck with me. Somehow, that seems like reason enough to recommend it be resurrected for some new readers in the modern era.

God's Demon

The depiction of Hell throughout history has been profoundly influenced by literary figures who have provided descriptions and imaginative representations of the concept. From ancient mythologies to modern literature, writers have shaped our understanding of Hell and its various manifestations, contributing to its multifaceted depiction.

In ancient mythology, writers such as the Greek poet Homer and the Roman poet Virgil laid the groundwork for the portrayal of Hell in Western literature. In Homer's Odyssey, the hero Odysseus encounters shades of the dead in the underworld, providing an early glimpse into the afterlife. Virgil's epic poem The Aeneid further elaborates on the underworld, known as the realm of Hades, depicting a place of punishment and torment for the damned.

However, it was perhaps Dante Alighieri who most profoundly shaped the Western imagination's understanding of Hell with his monumental work, The Divine Comedy. Written in the early 14th century, Dante's epic poem takes the reader on a journey through Hell, Purgatory, and Heaven, guided by the poet Virgil and his beloved Beatrice. In Hell, Dante encounters a structured realm consisting of nine concentric circles, each reserved for different types of sinners, with punishments befitting their crimes. From the gluttonous to the fraudulent, Dante's Hell is a place of unrelenting suffering and moral reckoning, immortalizing the poet's vision of divine justice.

Following Dante, numerous literary figures have continued to explore the theme of Hell in their works, each offering their own interpretation and embellishment. John Milton's Paradise Lost, published in the 17th century, presents a reimagining of the biblical story of the fall of Lucifer and his rebellion against God, depicting Hell as a realm of chaos and rebellion against divine authority. Milton's portrayal of Satan as a tragic figure struggling against his own pride and ambition has had a lasting influence on how Hell is perceived in literature.

I would argue it is hard to overstate the impact on the western world by Paradise Lost as a single piece of literature aside from the Bible.

In the 20th and 21st centuries, the depiction of Hell has continued to evolve, reflecting the changing cultural and philosophical landscape. Authors such as C.S. Lewis, with his The Great Divorce, and Neil Gaiman, with his Sandman comics, have offered imaginative reinterpretations of Hell, blending elements of fantasy, mythology, and existentialism to explore the nature of good and evil.

All this to say that I wish to speak about a man named Wayne Barlowe. Wayne Barlowe is a unique genius when it comes to depictions of Hell. Brushfire: Illuminations from the Inferno and Barlowe's Inferno are depictions not for the faint of heart showing a man who has seriously considered what it is to be tormented eternally. However, Wayne Barlow has also given us a rare treat in the form of a book I recently reread. God’s Demon.

If a demon, a fallen angel was truly sorry, would God take him back? That is the question at the heart of the novel. The answer to the question is best saved for the reader. Today I want to start with a 5/5 would recommend the book wholeheartedly even just as an exploration of a unique world that Barlowe builds. From the idea of soul bricks, humans reduced to nothing more than building blocks crushed underfoot by demons; to be a piece of construction material for all eternity. He layers on the idea that Hell was a place which existed before the fallen angels were cast there, complete with its own ecosystem and beasts which are a threat to the devils themselves.

Don’t get me wrong. The book is dark and not for everyone in that regard. Truly Dark fantasy. God's Demon, set in Hell, follows the fallen angel Sargatanas, who seeks redemption after millennia of serving Lucifer. As Hell crumbles under the weight of its own corruption, Sargatanas embarks on a journey to petition God for forgiveness and the chance to return to Heaven. Along the way, he encounters allies and adversaries, including other fallen angels and demonic creatures. As Sargatanas confronts his own past sins and struggles with the consequences of his actions, he must navigate Hell’s war-torn politics and confront powerful forces in his quest for redemption.

It brings up the old question, is it better to rule in hell or serve in heaven?

Go grab a copy, and get reading. The cover art alone should set your mind wondering. 😊

Beyond The Grave

I walked through a store the other day, and I was very confused to see a book on a new release rack by Terry Pratchett. A Stroke of the Pen: The Lost Stories.

To everyone who is a fan we can all say he died far too young, at the age of 66, in 2015. He undoubtedly had more tales to tell, and those tales which he did leave us have reached recent new popularity and revival by means of his writing companion Neil Gaiman and the BBC in the production of Good Omens. While I was less a fan of season two, found it less on point to Gaiman’s writing, it doesn’t detract from the fact that I loved his books, grew up on them and they were one of the group of pieces that formed my character.

I ramble but my point is perhaps, I could be justified in being surprised not quite a decade from his death that new Terry Pratchett books were available. To write to us from beyond the grave is a very rare treat. How many of us have a favorite artist, musician or author we would give nearly anything for one more magical piece?

Here we have dozens.

This is not what most people would have considered a normal collection. These were pieces he wrote at times under other names, extremely early in his career, and you can see the artist’s growth from just starting, to who he will become. Even the worst of them, are still clearly the same tone and same perspectives he will show us later as a more mature author, and honestly by the halfway point it is very clear that Pratchett had found who he was going to become. They are short, wonderful, whimsical additions to the Pratchett collection, and I couldn’t more highly recommend them.

To every author out there. If you have pieces half finished, and hidden gems, please leave them for us. Your fans will thank you for years to come. You never know, your fame may peak after you have decided to take a permanent nap.

Project Hail Mary

I have had Project Hail Mary sitting in my to read list for four to six months. As with all books I review on this channel I will never give a bad review. Not because I don’t read bad books, but writing a book is hard enough I never feel the need to denigrate any book publicly. With that out of the way you know if I am talking about a book, it gets at least a 2.5 / 5.0 from me. At least worth reading.

Project Hail Mary, by Andy Wier is somewhere in the realm of 4.3 / 5.0 for me.

I am a fan of hard science fiction. Science fiction, for me, should really ideally do one of two things.

-

It should inspire science. Real science. It should make people read the book, and think “Yeah, what if?” In the most positive possible way, it should make people think that science can in fact solve far more problems than it engenders.

-

It should make the reader think “Wait. What is happening with society here?” It can serve as a foil to show an error in real life by taking one specific portion of our technology to a point of reductio ad absurdum.

MINOR spoilers begin here.

Hail Mary is the first of these options, much like The Martian before it. Humanity is faced with the extinction of our species, and humanity absolutely comes together to solve the problem in a project named Hail Mary. Defined as “a long, typically unsuccessful pass made in a desperate attempt to score late in the game.” The probability of mankind succeeding in building a spaceship in a handful of years, sending it to a distant solar system to save our planet is indeed completely crazy.

The problems of real-life technology are solved in the book through means which are self-consistent. There are a few moments where you can see the mind of the author at work finding solutions to problems, but they are few.

If I am honest, around page 25 in my paperback version of the book, if it was any author other than Andy Weir, I would have called it quits. Why? Because there is hard science fiction, and then there is rock solid diamond hard science fiction. If you aim for the second but you are only the first, you will have plots and conflicts which demand detailed attention but you won’t give the reader enough detail to join you in the journey. Then what is left is silly, or trite or just so fantastical as to not be believable. I trusted him to deliver something hard enough, and he did.

Andy Weird pulls off the hard, hard science fiction, not flawlessly, but very, very well.

The main character makes a few mistakes that I don’t believe a trained astronaut would make, but the book makes clear he isn’t one, he’s just our best shot. I think the final twist was somewhat predictable. Not what it was, but that it had to happen. I was at 90 % waiting for the shoe to drop, knowing it had to, and then it landed.

There is in my opinion one glaring error scientifically which is never brought up or addressed, but again, I am okay with that. Because the book is fun. You want to know what happens, and how the problems get solved.

MAJOR spoilers begin here.

The book is also a rare example if a nearly 100 % conflict based in humanity versus nature. I call this a major spoiler because I spent the entire book waiting for there to be conflict between some of the characters, but it blessedly never happened. He stuck to his guns and kept this a Person Vs. Nature conflict.

While there are characters in the book who don’t agree, or get along in all cases, the true conflicts of the book feel solved by cooperation and “We have to get this done,” attitude. It was frankly very refreshing to know that there is an author who believes humanity can come together to solve its problems with the collective abilities and knowledge of our species.

For me, it didn’t make the book simple, it made the book more fun.

Overall, Project Hail Mary lands a strong should read recommendation. 4.3/5.0.

Stolen Earth, by J.T. Nicholas.

This is the first novel I have read by J.T. Nicholas and for a quick summary, the book hits many of the standard science fiction adventure notes. This book is not quite hard science fiction though it leans in that direction with hints of Star Trek terminology thrown in, like shields and deflectors.

The title is what grabbed me. The idea of stealing a planet of course sets up enough curiosity to flip the book over and check the back cover. As blurbs go it was a mix of the semi standard post apocalyptic prediction that we will destroy our environment, but the second note is what made me give the book a try. AI’s drove humanity off the planet, and we live in fear, with all guns pointed at earth to keep them there.

Now the flap also immediately gives us the statement that a crew makes it to earth, and finds out not everything is what it seems.

Could it be no Ais at all? Peaceful AI’s? Long dead?

Other questions nagged at me enough to pick it up for a read, which included how did we live without earth? The year is not stated on the back cover, so I wanted to know if we lost the planet before or after we had established ourselves on other rocks.

The book answers all of it.

If you are expecting an older fashion science fiction with a slow burn like Arthur C. Clarke or Orson Scott Card, this is not the book for you. This had a feeling more in line with the TV show Firefly, featuring space cowboy vibes.

The book opened weakly with a prologue that you will need to push through. It's exposition, and ultimately not tied directly to the story, but after that it picks up fast enough. A crew will be forced to work together to make it to earth for a payment so staggering they can stop being pirates. While setting up the heist structure the book lets us know the back story.

Mankind set up AI’s to run the militaries of the world. Six of them, called the big six are said to be the USA, China, and the others are left vague. At least one ruled over South America. Russia is implied. In fear we don’t want “unfettered,” AI to escape. True full artificial intelligence. All other forms of AI are banned in the Commonwealth, so that mistakes are not repeated. The Commonwealth is painted as fairly totalitarian, and while not an unpleasant place, certainly not a pleasant place to live. Then again, we are locked into perspectives of people who live on the fringe of that society, as thieves and freelancers.

We learn through the story some members of the crew are not who they seem, working for the commonwealth, or are ex-Commonwealth scientists itching to get their hands on a live AI, and at least see what they became.

Through hijinks, a touch or two of serendipity and author fiat, they make it to earth.

I won’t lie, I was fully expecting the AI to be cuddly, not at all violent, and the entire thing to be a mistake, or a lie as the story twist. I would have been disappointed. Fear not, these AI's meant business. On landing they are attacked within minutes by swarms of nanobots, against which they have precisely no hope of survival. They flee, lose the fight are put into submission from air toxic to life and ultimately wake up after being rescued by other humans.

People have survived and adapted to life on the planet. Without going into the nitty gritty, the ideas are actually pretty high science fiction. Everyone one the planet has nanobots in them which enable them to survive the environmental attacking nanobots, and each region of earth has an AI which is looking after it.

At this point the book breaks off into a completely new storyline. The notion of the heist was a McGuffin to get them to the planet, so more of the tale can actually start. They meet an AI, and here the author runs into the same problem any writer will when dealing with characters who are smarter than us. How on earth do you write them? Whether it’s a 1000-year-old person, or an artificial intelligence that has been running non stop for a hundred years perfecting whatever it wants, how can we possibly portray it? His approach is generally minimalist.

We do not hear much from the AI’s perspective, and the interactions are kept fairly short. They are fighting one another, and have been since humanity left, but they don’t want to anymore. They were never “unfettered,” AI. They were slaves to a program which required them to fight to the very bitter end, but since nobody was left from the military to tell any of them to stand down, they continue on their destructive path. They are asking permission to be set free to do whatever they want… Specifically stop fighting.

Of course, this paints the conundrum, what would an infinitely amazing intelligence with all the weapons in the world do with that freedom? What would the three remaining AI’s do collectively now that a hundred-year war is finished? Humanity had always pointed every weapon at the planet, but their reason was wrong. What if they suddenly found out it was true?

This is the question which preoccupies the last third or so of the novel and it is a question worth exploring. The tone and the focus of the book doesn’t give us much to go on from the AI’s perspective, I think intended by the author to leave all of the arguments to the people, who are split on the decision. The AI's promise them “We are nice, honest.”

I won't spoil the entire ending, but I will say it was worth the read. The novel is a quick, and all things considered, light read. Perhaps fun is the best way to explain it, though I felt a lot of possibility was left on the table. If you’re looking for a book to read on the train, or a flight, this is the kind of book to grab.

Rating: 3.2 / 5.0

Illegal Alien

by Robert J. Sawyer

Robert J. Sawyer is one of only eight writers to win the Hugo, the Nebula and the John Campbell Memorial Award. If you have not heard of him, then you are missing out on some of the best science fiction to be written in our generation. I first encountered his works in The Neanderthal Parallax. A good and a bad thing, because it remains to this day my favorite of his works. Its almost a shame to come out the gate with the best, but let me say unequivocally I have never disliked single book he has written.

This book review, about Illegal Alien, is late to the party. Very late to the party. Twenty five years really. Published in 1997, I didn't notice the existence of this book until this month, when I was looking through front covers of other books and saw, a title I did not own and had not read. I had to rectify it immediately and I did not regret it.

The premise is captivating of its own accord, and is the meat of a lot of science fiction. Humanity is not alone in the universe, we meet aliens ... things happen. Many science fiction readers will be a long for the ride for this reason alone. As the cover says, an alien kills a human, and now they have to stand trial.

Let me get the few things out o the way that my personal opinion keep this book from being a solid 5/5.

I had trouble suspending disbelief for a time that a) government agents are not with the aliens 100 % of the time. b) that any first contact situation which resulted in murder would be anything other than covered up completely at any cost.

Spoilers begin here...

The book addresses these to some degree. The had already been on earth for quite some time. Many months have passed since first contact, peaceful introduction to the united nations, and an ask for help from our galactic neighbors, the Tosok race, who come from alpha centauri. while hype has not exactly died down, a certain sense of normal has settled in about them. They are more advanced than us, but not unimaginably so. They damaged their ship entering the solar system.

so why after all those months did one of them kill the Carl Sagan character of our time?

The use of trial structure, is a very fun blend of genres and a mystery wrapped into the discovery of the functioning of a different race is top tier. One of Sawyers hallmarks, for me, is that his alien races when used are not human.

When you watch a star trek, or star wars, even if other races have fish heads or an extra set of limbs they are human like. Their values and beliefs and basic structural needs are so like our you understand there is a human behind the mask. Sawyer creates through the exploration of motive and action an alien race which is believably other.

They do not have the same belief structure we do. They do not have the same taboos which we do. They do not have an anatomy anything like ours, or a culture anything like our. This trial shows the differences in assumptions, and the differences in fears and wants that the Tosok experience in comparison to us.

As always the writing is fluid, letting pages fly past while you want to know who did it.

The book is unquestionably structured that ONE of the aliens committed the murder, but because we discover along with the jury much of the evidence we want to believe the lead alien character Hask did not do it.

You will learn the answer to it all within the last 3 chapters, as the books structure keep you wanting to know more to the very end. Sawyer, as ever is a master of promising something early in the book, and delivering by the finish line.

Rating:

4.3/5.

Made to Order: Robots and Revolution

I had never read a short story collection until I was over twenty. Strange to some avid readers I know, but I had a feeling that I didn’t want to get into a world, just to have it snatched away from me quickly, so I generally avoided short stories all together. I have found now, both as a writer and a reader, that some stories are just not meant to be long form tales. Sometimes there is an idea which is short, concise and simply needs to be said. Enter, the short story.The other advantage to short story collections is the introduction of a new author to my book horizons. This collection was no exception. I don’t want to ruin these short stories with too many spoilers so I am only going to cover about a third of them, and some I am going to let slide the big reveal.

Test 4 Echo, by Peter Watts

This is a story about a probe exploring another section of our solar system which runs on AI systems of generally low caliber of the era. This story is hard science fiction. The science is grounded in reality, understandable, even if beyond our current abilities, and feel gritty. The story managed to maintain tension, despite the story’s implication that the main characters are physically safe. The main idea is that each of the arms of a spider bot, run on independent AI system to work together toward common motion and goals. One of them becomes more sentient than the rest. This brings questions into the story of, can we reprogram it? Does this one arm have rights? There are hidden gems throughout this one. It has relevant and poignant discussions about the nature of AIs, what rights they have, and how we build them. What is it like without them and with them? How do you and can you, reset one? This is enough to make me say I am off to buy his Firefall novels.

Brother Rifle, by Daryl Gregory

Much about this piece feels when you first dig into it, like old ground, and you think you know where it is going. It is well done, and beautifully written but has a vibe of the familiar. Until, it doesn’t. The subversion of story arc in this short piece is very well done. This is not the war veteran story you think it is, it is better than that. What is war like in a world where soldiers have implanted AI in their brain as tactical systems? What does it mean to have a feeling of rightness about a decision? This is used to ask questions about retraining the brain using AI, based on an averaging model structure. But if you become the average of those around you, who are you? Can you still, be you? The structure of the story uses flashback more effectively than most anyone pulls off, especially in a short story.

Idol, by Ken Liu

It is not often a person can lay claim to creation of a genre, though many say that Ken Liu did just that in defining his novel structure as SilkPunk. I will say that my memory is that similar Asian based steam punk aesthetics existed prior to his work in the teens, nonetheless there is a certain unique feel to his writing. This story feels very real life adjacent, and uses technology and ideas which exist today, right now to paint questions of how we should use AI. The main character has the ability to speak with their dead father, reconstructed like a chatbot through their online information and left over data. The hook here is beautiful. “I am talking to my father. I’ve never met him, and I never will.” It begs questions and it does answer them. What else would exist in a world with this idea of a modeled person? How would famous people interact with the world? How could we mine data you place in the world and use it to learn about you, both to your benefit and to your detriment? The story has great use of perspective changes, great cadence changes, and is a tacit warning to everyone to be careful what you put out into the internet. It can come back to bite you.

Bigger Fish, Sarah Pinske

Spoiler alert! Skip this one if you don’t want to know the ending. This is a solid opening piece setting the amazingly mixed mood of film Noir, and future science fiction dystopia concurrently. A stage s set for water tycoons, and water reserves treated with the respect of gold. The old feel gumshoes and private investigator vibe is strong and used to great effect. The troops are leveraged when needed but not leaned in to, too hard. Despite being a short piece, it caught me because I felt like... finally, a protagonist, who found out the answers, figured out the who-dun-it, and decided, they had bigger fish to fry. They let the bad guy go, and it has every element of realistic, and plausible.

Polished Performance, by Alastair Reynolds

As the author I have read the most from the collection in terms of previous novels, I thought I had a feel for the tone and vibe that I would get from this story, but it felt lighter hearted than some of the other pieces by Reynolds I have read before.

There are a pair of scenes in this story whish made me legitimately laugh out loud. It is a very odd voice in the story in terms of perspective. The story opens with clear deliberate exposition, but it is done well enough to be not off putting. There are robots on an interstellar voyage. They have clear personalities and hierarchies. Unfortunately, their passengers are dead, and they need to figure out what to do, with only a fifty-year ticking clock. This asks the question how much will an AI do to stay live and defend themselves? How much is a person just meat vs a collection of memories? This pokes fun at human and human like behaviors in very amusing ways, and as always for his works, delivers.

An Elephant Never Forgets, by Rich Larson

I am going to come right out and say this was one of two pieces in the collection I actively disliked. I am mentioning this piece however because it achieves something incredibly rare. A very well written second person perspective. To tell a reader “You,” and place them well and believably in to the shoes of the character, is extremely hard but it is done here successfully. The story has dramatic word choices which set strong tones, like piss yellow, acid green and blood red. However, the tone it set was too dark for my taste. There are many child size objects and childlike murder perspectives. It felt like "too much," for "too much," sake. It felt like horror more than science fiction.

Sin Eater, Ian McLeod

This is another of my favorite pieces and unfortunately (for me) another new author, whom I come to far too late, and have to go by more of his works. The premise is simple. What happens when the last person on earth, meets the last sin eater at the time of their death?The story has a very strong opening in the empty stretches of suburbia. Rome specifically. It is in ruin, and the choice is so beautiful as a city that in our present day is itself build on the ruins of the old, and celebrates its own history. The last survivors in its streets are roots. Humans have ascended to other places. We have merged in a single conscious virtual reality. A digital afterlife. The reason I love this story is because this tale led me to think. I have always believed the best science fiction makes us wonder about the what if? What if you could make your own heaven? What if you could carve away at pieces of yourself, and crate a perfect version of yourself to live on beyond your current versions. Would you? How do you reconcile the heaven of the three pillars of monotheistic faith, with the heaven which is tangible and real, and can be touched?

The book collection on the whole is worth a purchase, without question. The majority of the story are well written, and its always wonderful to find new authors, but this collection as a whole left me thinking. Why do we write science fiction? Why do we read it? When I was growing up, I felt like since fiction was about the what if, for what humanity could become, and do. It was a hopeful, of difficult road leading to somewhere. Today I fee like so much for the science fiction we consume is about the things we fear. They are a warning to the future versions of ourselves, to say, look out. This is a book that is filled with dystopian futures, and post-apocalyptic dreams of a world without water, or privacy, filled with terrible city shattering storms and ever-increasing divides between the rich and poor. There is little hope found in these pages. I am not sure when science fiction became so hopeless. Maybe it isn’t all this way, but this collection had that feeling. Not a question of what can we do, but more the feeling of a mother scolding, what did you already do?

Final verdict: 4.0/5.0

Amped

By

Daniel H Wilson

I am a fan of the author Daniel H Wilson, having discovered his work first though Robopocalypse, and then through The Clockwork Dynasty.

When you discover an author if you are like me you start to read everything the author has every written, so it was with joy as I walked through a book store and I saw his name on the book Amped. One of the items that caught my attention was not only the author name, but the enjoyment as a scientist of reading science fiction from a decade off, and seeing how close the author got to correct science.

In fairness, the exact year is never stated.

What if humans were augmented with chips, that allowed us to become more than human? Control extra senses, think faster than we could before, even things that we would consider superhuman today?

The technology in question has existed for a number of years at the beginning of the story, and sets the stage for the questions of what if in this book.

Amped uses an epistle style entry at the beginning of every chapter. Sometimes these are news clippings, sometimes headlines from TV shows and web pages, other times pages from law briefs. I have always enjoyed these especially in first person stories, which Amped is, because it gives a perspective wider than the narrator’s own limited view.

The first chapter opens with the tone of the book that will keep on throughout. The book uses the small to teach about the large. The main character, Owen, is a school teacher, and an Amp, who has to watch another one of his students commit suicide. No spoiler here, it is told in the first few pages of the book.

It was a well-done opening, gets people invested in the character, and the world, but it does immediately beg the same question I have always had for books of this type, and movies. X-men, and magic worlds often beg the question for me, that without serious price for the magic in question, why would the super beings not have more worshipers, than retractors, or people who want to join the group, than not?

Throughout this is addressed, though only tertiarily.

We follow Owen through his trials as an Amp as the world begins to turn the legal tides against superhumans, at least in America. This differentiation is hinted at in other parts of the book too, but never take center stage. What is Europe doing? What is China doing?

Light spoilers ahead!

Around the one third mark we see the real action inciting incident. Until this pint Own is a passive observer for us as the audience to see the world, and experience hat it might be like to have the majority of the world decide you have no rights. What if tomorrow you have no property rights? No marriage rights? No citizenship of any kind? Who would remain your friend? Who would stand with you against the tides? Who would steal from you? Who would hurt you?

This hatred and physical harm against a child who is also an Amp is what drives Owen to action.

While the tugging at heartstrings is reasonably well written, the level of visceral hatred is at times a touch disingenuous, and the rate of decline in the level of society’s standards is not easily believed. Laws are passed in days not weeks, and violence erupts in a matter of days, not months. However, as a book, which is always a shortened caricature of reality, it is looking to invoke an emotional response. Which it does. By the one third mark many readers will be thinking, “if the Amps are so dangerous, why aren’t they fighting back? I would!”

From here we get a somewhat standard hero’s quest, and the chosen one structure granted power by destiny. In this case by his father’s technology, who has to figure out the good guys and bad guys in a landscape of violence.

We see some variety in characters, including kids who beg for implantations, because they want to be special too, Amps who are rising up to lead the other Amps in a civil war against the pure humans. Glimpses of the president starting internment camps, complete with trains dropping off people for “Their own protection,” round out the World War II era vibes and the core question is offered up, that with this power, the true nature of a person comes out. Will our hero kill? Will he be good or bad?

We are unfortunately not treated to many viewpoints in the story. A character who is perhaps wisest doesn’t get much page time. The Amp’s Messianic character is a touch too one dimensional, and smacked slightly too strongly of a Vietnam veteran trope.

We are treated to some double crosses, and the answer to the question, what will Owen do to protect the world he loves?

All told, the story lives up to the cover of the book, “A fast-paced narrative.” The book is a very quick read, in my version at only about two hundred seventy pages. While it was entertaining it lacked the depth I have associated with the author's other works at times, and left me wishing it was longer, for a better harder hitting piece.

Conclusion? 2.8/5.0